Guest MOC interviews series

Flufy

DESIGNED

2024

INVENTORY

1500 parts

THEME

SUV

Hi,

I’m Attila, but in the LEGO community I go by the name of Attika.

Like almost all of us, I was playing with LEGO in my childhood and, as commonly happens, it ended around my early teenage years. The so-called dark age lasted until 2011, when I bought a Technic set (8081) for my nephew who, at that time, was waaay too young for it – so I opened it up. Just like the mythological Pandora’s box, this box opening had an irreversible effect and set my future up for good in terms of hobbies… I was mesmerized by the new elements (differentials, suspension arms, etc.) and my brain instantly started to combine them, like that 15–20 year gap had never even been there.

Video

The first few years I spent building in all my free time and reached all the goals I remembered having in my childhood – but this time I had parts that did not exist back then, or that I could not afford.

After a while, however, some mini dark ages came again, with all the worrying thoughts: “That was it?” But always a new idea or inspiration brought me back to the table.

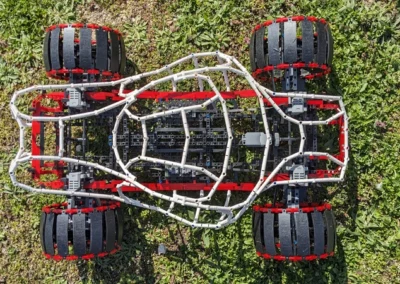

Fluffy came into existence after a similar dark period. I bought two sets of the 42160 Audi, as it was a remarkable pack of parts and electronics. Now, it’s worth mentioning that I rarely use panels in my builds. I have a reputation for a connector- and liftarm-based building style. With the Audis came a number of 13×3 curved panels, and I could try out an old idea that had been lurking in the back of my brain for a long time.

Using no.3 connectors and these curved panels, I pictured a barrel shape. Since I hadn’t had enough of these panels until that time, I had no opportunity to test the idea.

A side note here: I don’t design digitally. I find it very misleading as it doesn’t give me any feedback about the physics and behavior of a given build. I like to get my hands dirty with plastic, as it tells me right away if an idea is worth the effort of developing or not. We shouldn’t forget that ABS is – at least to an extent – flexible. This attribute can be a curse as well as a blessing, but no digital building platform can model that.

Back to the “invention of the wheel” (a little presumptuous, I know :-D) –

I had the full barrel shape and it was more or less as I imagined it. The next step was to figure out the inner structure. I needed something in the middle to attach to a regular 3-pin wheel hub and a framing that would keep the whole thing together. A few hours and a sprocket wheel gave me a satisfactory outcome, and I had a larger-than-ever Lego wheel in my hand.

It rarely happens, but I did not think ahead. I just realized at that very moment that I needed four of these wheels and an oversized chassis to test them. So I sat down and made a big BrickLink order. Once it arrived, it took only a couple of hours to put the wheels together and make a temporary chassis. (I wasn’t even sure if the wheel hubs could bear the weight and the size of the wheels at all.) To make it move I used four BuWizz motors, one in each corner of the chassis, and – having only three BuWizz 3.0 units – I used two of those to give the sparkles.

In the first test I used the slow output straight to the planetary wheel hub and, to my biggest surprise, it worked smoothly. Not only did the electronics hold up, but all the mechanical question marks were answered positively. The wheels didn’t fall apart, didn’t even fall off from the wheel hubs, and the whole monstrosity was just rolling around peacefully. It’s rare to feel that much satisfaction. In my head there had been about ten points of failure that could break the whole project, and none of them turned out to be true or unsolvable.

From this point it was easy to go ahead. Anyone who has ever designed a Technic car knows that the hardest part is the front suspension, especially when it is driven as well.

In this case, however, I had a wheel with an inner diameter of 20 (!) studs. I never, in my career, had an easier task to make a proper suspension geometry. Since the official dedicated parts are way too small, I made “brick-built” proper triangle-shaped suspension arms, which I could design to get the desired camber and caster angles. Ackermann geometry was just as easy to implement, and I still had an airport-sized area free inside the wheels.

Later I recognized that all this geometrical accuracy was far more necessary at this size than it was in regular-sized models. Due to the aforementioned attributes of ABS and the nature of the connections, this build really scraped the limits of what the material can bear.

With the chassis done and tested, I got to the point where I usually freeze – bodywork.

I know it sounds stupid, but I’m not good at it. Not because of the outcome – that mostly comes out just fine – but (and I wasn’t ever able to put it into words until typing these very characters) because I have no concept in my head.

Whenever I want to build a chassis, 90% of it already exists in my head; I just have to put it in plastic. But when it comes to the bodywork, usually I just start to put parts together and make it up as I go. Same happened here. Luckily I’ve built up a respectable size inventory of connectors in the last 15 years, so I did not have to compromise on the shape as it came to life.

As I mentioned above, our ultimate barrier is the material. I knew I had to keep the weight as low as possible, so this connector-based wireframe bodywork was the right way to go.

When the last of the white connectors took its place, it was all done. Fluffy was born – 70 cm, 2.3 kg, and healthy. After I tested the finished model, I was tempted to change the motor output to the fast one. I didn’t think it was going to last, as my former year’s BuWizz Gathering Ultimate Off-roader was set up the same way, having half the weight on half the size of wheels. But again, despite all the odds, Fluffy was gracefully hovering around my moderately grassy fields with no problem whatsoever. And the rest is history…

Wherever I took Fluffy, after a few rounds, people kept asking: “Will you build a bigger one?”

My answer is a resounding no.

This build really represents the limit of what plastic can endure. I got challenged to use turntable-based wheel hubs so it could take more weight. That seems to be true, but if we leave aside the friction it generates and the extra electronics it requires, in all aspects the model would need to be reinforced in that case. That is weight in itself, so all I’d do is give it more weight so it could hold its own weight. I have the gut feeling that by pure luck and coincidence I’ve found a very delicate balance in size and weight that is still capable of achieving an enjoyable speed.

I might be wrong – and if you, dear reader, feel like you want to pull a card on that 20, I’m looking forward to seeing the results. The wheel is invented, the rest is up to you…